|

|

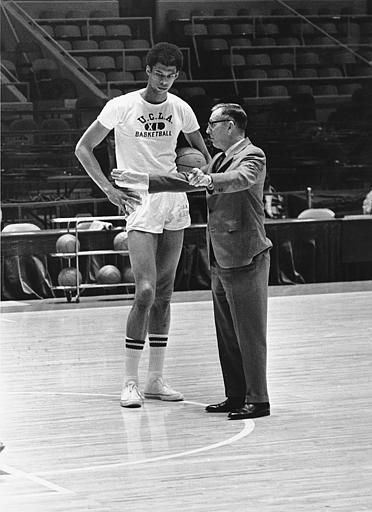

What is a Coach?

A sports coach will make

you run more laps than you feel like. A sports coach pushes an athlete to achieve

optimum performance, provides support when the athlete is exhausted and teaches

the athlete to execute plays that the competition does not anticipate. A sports

coach will tell it like it is.

The role of the Business Coach

is to coach business owners to improve their business through guidance,

support and encouragement. They help the owners of small and medium sized

businesses with their sales, marketing, management, team building and so much

more. Just like a sporting coach, your Business Coach will make you focus on the

game.*

A Bible Coach makes you

read the Bible more than you feel like. A Bible Coach pushes you in the race set

before you (Hebrews

12:1; 2 Timothy 4:7), helping you apply what you read, building personal

habits, overcoming defects of character that keep you from winning the race and

being awarded an imperishable crown (1

Corinthians 9:24-25). |

| Here are the opening paragraphs from an article in The

New Yorker, April 22, 2002 v78 i9 p114(11) entitled, "The

Better Boss: How Marshall Goldsmith Reforms Executives, by Larissa

MacFarquhar. |

Abstract: Goldsmith's career as an executive

coach who trains executives to be respectful of others to help in employee

retention and formation of strategy. His techniques and some case studies are

described. |

Marshall Goldsmith's official job

description is "executive coach": he trains executives to behave decently in

the office, by subjecting them to a brutal regimen. First, he solicits "360°

feedback" -- he asks their colleagues and sometimes their families, too, for

comprehensive assessments of their strengths and defects -- and he confronts them with

what everybody really thinks. Then he makes them apologize and ask for help in getting

better. It's a simple method -- "I don't think anybody's going to say I'm guilty of

excessive subtlety," he says -- but it works. It had better work. If it doesn't,

the client gets his money back.

Goldsmith won't take on a client who doesn't want to change -- someone who, as he

puts it, has not a skill problem but a don't-give-a-shit problem -- but, short of that,

the more obnoxious the better. "My favorite case study was in the 0.1 percentile

for treating people with respect," he says. "That means that there were over a

thousand people in that company and this person came in dead last. This person would be

in an elevator and someone would come up and say, 'Hey, how's it going?,' and he

wouldn't even respond. He was hardworking and brilliant; he didn't lie, cheat, or steal.

He was just a complete jerk. The case was considered hopeless, but in one year he got up

to 53.7 per cent.

"You know how I helped the guy to change? I asked him, 'How do you treat people

at home?' He said, 'Oh, I'm totally different at home.' I said, 'Let's call your wife

and kids.' What did his wife say? 'You're a jerk.' Called the kids. 'Jerk.' 'Jerk.' So I

said, 'Look, I can't help you make money, you're already making more than God, but do

you want to have a funeral that no one attends? Because that's where this train is

headed."

What is Coaching?

See what other coaches say

|

|

|

When Goldsmith started executive coaching, in the early eighties, he was a pioneer.

Coaching really came into its own as an industry about five or six years ago, when

employee retention became a serious problem. Prosperous baby boomers were retiring

early, and members of Generation X were looking for variety and fulfillment rather than

security. Human-resources departments, meanwhile, were calculating the cost of losing an

important employee (between one and two times the employee's annual salary and benefits,

according to one estimate), and had discovered that one of the two main reasons that

people left jobs was that they hated their boss (the other being the general failure of

the company). Clearly, it was foolish to lose talent for no better reason than that a

vice-president appeared to his subordinates to be insufficiently interested in what they

had to say. Moreover, a bad attitude on the part of senior management was held to be

detrimental not only to retaining employees but also to the formation of strategy. The

old-fashioned leader, with his bulldozer personality and his single-minded certainties,

was thought to be too arrogant to lower his ear to the ground and listen for changes

coming. Thus, the executive coach.

Coaching being still in its chaotic, juvenile phase, there are, as yet, no licensing

requirements of any kind. Anyone can call himself an executive coach, and thousands do.

Schools are springing up everywhere: Coach

Universe and Coach U conduct classes

by phone; CoachVille.com

trains coaches for a seventy-nine-dollar lifetime-membership fee. For this reason,

first-to-market coaches like Goldsmith, who already have solid reputations and have

received notices in the business press (he was listed as one of five top coaches by Forbes,

and in the top ten by the Wall

Street Journal), are flourishing. Goldsmith's current clients include

ChevronTexaco, Motorola, Thomson, and Pitney Bowes. Some executives remain suspicious of

coaching, thinking of it as a reproach or as enforced psychotherapy, but more often

these days the offer of a coach is taken as a compliment -- a sign, since the service is

expensive, that a person is being groomed for significant promotion.

One of Goldsmith's clients is an executive in a large corporation. He is high-ranking

-- only a step or two from the top. None of Goldsmith's clients are far from the top --

his services are too expensive to waste on mid-level managers. (He won't say how much he

charges, but it is reported to be in the high five figures per client per year, which

makes him one of the best-paid coaches in the field.) On a recent visit to the

executive's office, Goldsmith ran into his client in the hallway, where the two of them

were spotted by a little white-haired man wearing a red bow tie.

"Who's getting their head shrunk today?" asked the white-haired man in a

jovial tone. The executive gave him a pained smile.

The executive was in his early forties and wore an open-necked white shirt. He had

the genial, Saturday air of a man with a beer, making a seamless transition from

fraternity to barbecue -- an air that, by all accounts, had served him well in his work.

But, at the same time, there was a tense wariness about him. The people in marketing who

worked under him thought he was terrific, but his peers were tired of what they felt

were his incessant competitive put-downs, and people in sales felt that he had failed,

as Goldsmith primly put it, to treat them like customers. The executive had to stop

being so territorial, the C.E.O. decided. Goldsmith was called in and signed up for a

year.

* Paul

Fagan